Round 2 of The Open is complete:

- Tiger Woods missed the cut by 9 strokes with a 78-75 and said “This might have been my last Open at St. Andrews.”

- Phil Mickelson wasn’t much better at 72-77.

- Defending champion Collin Morikowa came within a stroke, but also missed the cut.

Australia’s Cameron Smith shot a spectacular 64 to take the lead. Renegade superstar Dustin Johnson, probably the brightest light of the LIV tour, stayed in contention, four strokes back at 68-67.

—

Tiger is 46, and may not have been competitive even without the damage from his accident. 46 is getting up there for a major champion.

The oldest winner of a major was 50, a record set last year when Phil Mickelson won the 2021 PGA. The PGA is the only major that has ever been won by a player older than 46.

Jack Nicklaus won his last major at 46, when he became the oldest man to win the Masters.

The oldest winner of the U.S. Open was Hale Irwin at 45.

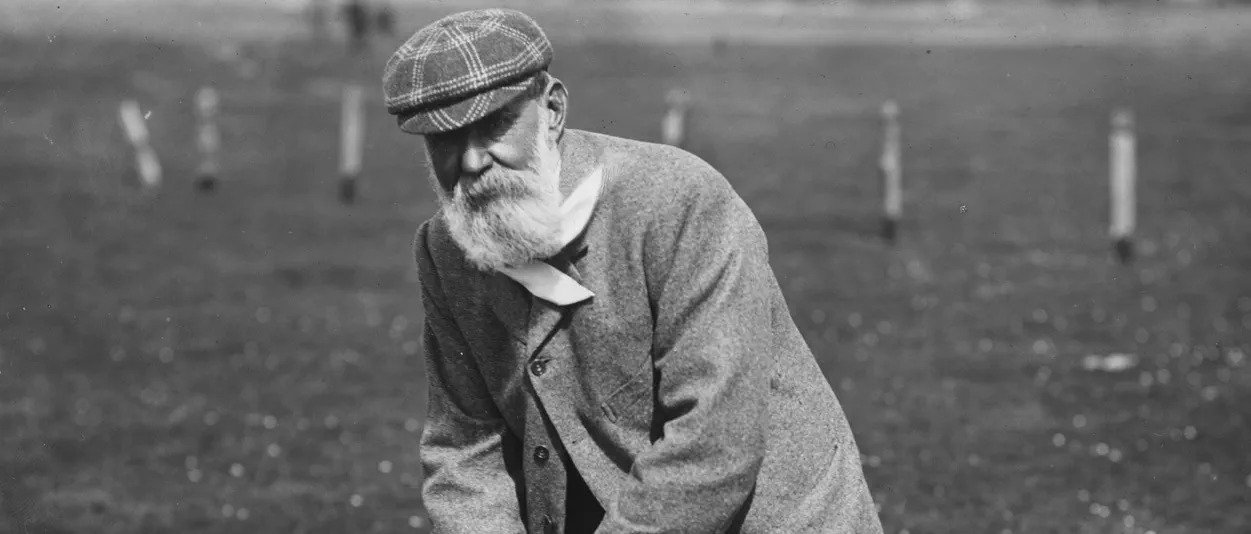

The oldest golfer to win the British Open in modern times was 44 (Roberto de Vincenzo in 1967), although some old white-bearded codger won it at 46 in 1867, when they used to play in tailored suits and dress shoes.

That 1867 win was quite an achievement, given that 46 was a ripe old age by the standard of that era, about equivalent to 117 today. Of course, that win could possibly be attributed to the fact that only two guys played golf in 1867, and the other one was blind, and had been declared legally dead (although, to be fair, he did appeal that ruling once somebody read it to him).

Kidding aside, there really were only fourteen entrants in that tournament. The winner shot 170 for 36 holes and won a whopping seven quid. Only four of the fourteen entrants won any money at all, and the fourth place guy only raked in a single pound for his efforts.

(One pound in 1867 is roughly equivalent to the purchasing power of £124 today.)

I don’t know anything about anything, but I think this year’s Majors are it for Tiger. He’s just too injured (probably permanently) to walk those courses. I can’t believe he made even one round at St. Andrews! That place is all mounds and hills! Like post said, he’s too old and I believe it’s going to take a couple years more of rehab for Tiger to really be able to walk those courses. He doesn’t have the time to recoup at his age.

Given the foregoing controversy, I will refrain from asking how fingers fing.

Even tho we are all pretenders to writing, speech is the primary mode of language. And, orally, “old white-bearded old man” passes unremarked all the time.

Y’know, they call them codgers, but when do you ever see them codge?

“Codger” means “old man,” so “old codger” is a redundancy. Just saying.

Not exactly right.

“Old codger” is an idiomatic expression. It has been for centuries, since before America was a country, and has been used as a self-contained idiom by such luminaries as Shelley. In fact, per OED, the term “old codger” appears in print before the unadorned “codger.” In fact, when used to mean an elderly man, “codger” is not often seen unless preceded by “old.” That idiom/cliche may have developed to distinguish the “elderly fellow” variant from the second meaning, when the word “codger” flies solo and simply means “a fellow.” Note that when Dickens used the world “codger” in Nicholas Nickelby, he did not mean “an old chap,” but merely “a chap.”

OED’s entry:

1. A familiar or jocosely irreverent term applied originally to an elderly man, usually with a grotesque or whimsical implication.

1756 Murphy Apprentice i. (1764) 16 Old Cojer must not smoke that I have any concern. 1775 Garrick Bon Ton 32 My Lord’s servants call you an old out-of-fashion’d Codger. Ibid. 33 That for you, old Codger (snaps his fingers). 1789 Wolcott (P. Pindar) Subj. for Painters Wks. 1812 II, We want no proofs, old Codger, but your face. 1807–8 W. Irving Salmag. (1824) 89 A gouty old codger of an alderman. 1821 Shelley Let. Mrs. S. Aug. (Camelot ed.) 355, I‥sign the agreement for the old codger’s house.

2. In more general application: fellow, chap.

1839 Dickens Nich. Nick. lx, ‘I haven’t been drinking your health, my codger’, replied Mr. Squeers. 1851 D. Jerrold St. Giles’s 23 (Hoppe) And that’s what they’ll do with you, my little codger. 1883 Hampsh. Gloss., Codger, a name given when familiarly addressing an acquaintance.

I would assume that the word “codger” had the original meaning of “man” (or something else as yet undiscovered by etymologists) which necessitated “old codger” to distinguish a more specific type of man, and after a while “codger” was able to stand on its own as “old man.” But that’s just me guessing, and it’s a guess that I can’t support, given that the “old” prefix was already there in the first several appearances of the word in print (beginning with “Old Cojer” in 1756), while the first appearance of “codger” without the “old” modifier didn’t come until some four decades later.

What he said!

A lost gets lost to the mists of time. Petrified fossils seldom leave much to glean in the way of soft tissues. Something like the history of brain structure such as functional precursors to what’s now Broca’s area seems unlikely that we’ll ever be able to piece together.

Similarly, to codge might have been a little-enough used transitive verb that happened to be, say, a habit of elderly fellows. Associating old & codging might’ve been quite natural & using the two together happened organically & consistently, without them ever really being used separately. The later isolated use of codger by itself could simply have been a back-formation. Pent-house, for example, is a folk etymology re-interpretation of “pentis”.

Ach! “A lot gets lost…”

I will concede that “codger” doesn’t necessarily have to mean “old,” although it virtually always does in modern usage. As for the word’s etymology, I’ve seen several attempts to link it to the archaic word “cadger” (an itinerant peddler), but it’s mostly speculation, which is almost always worthless in word-origin circles. The dumbest suggestion is that “codger” is short for “coffin-dodger.”

I guess the point is that the term “old codger” seems to have preceded the word “codger” into the language, so it is basically a fixed phrase like “join together,” as opposed to a solecism like “actual fact.”

Re coffin-dodger:

When studying etymology, it seems wise to assume that –

1. Nobody really knows anything.

2. Those that claim to know something are probably wrong.

Of course I am exaggerating, because some words can be traced to Latin or other ancient origins, but I find it useful to assume those two premises. Etymology, more than any other field in my experience, requires intense skepticism, and any conclusions usually must remain tentative and laden with caveats. Unlike most fields of scholarship, it’s a field where digging deeper seems to push a diligent researcher farther from certainty. As the cliche goes, the more you know, the more you realize how little you know. People crave simplicity and clarity, and to that end pepper their scholarship with speculations, like codger from coffin-dodger or goon from gorilla-baboon. While those theories may sound reasonable, they are rarely accurate because simplicity and clarity are the enemies of accuracy in this field. Word origins tend to be complex and frustratingly murky.